Epilepsy Program in Malawi

Contents

- Epilepsy training in Malawi: developing the WHO Intersectoral Global Action Plan 2022-2031 on epilepsy

- Continuing the work in primary care: task shifting, task sharing, training on-the-job. Facing real life issues: patients stop taking antiepileptic drugs; epilepsy and pregnancy

- How care for patients with epilepsy is changing

- Perspective of patients with epilepsy in Malawi with a look at sub-Saharan Africa

The antiepileptic drugs

-

- Spending on antiepileptic drugs

- The drug market

- The HIV/AIDS story in sub-Saharan Africa can show a path also for epilepsy

If the problem is circular

-

- Drug shortage limits adequate training

- Mental illness and epilepsy

- If awareness goes with care

Epilepsy training in Malawi: developing the WHO Intersectoral Global Action Plan 2022-2031 on epilepsy

The epilepsy program at DREAM started in Malawi in 2020. So far many teaching courses and repeated training on the job periods to allow appropriate task shifting through task sharing have been done. In 2021 a video EEG was donated by the Italian Society of Neurology and installed at the DREAM centre in Blantyre. EEG recordings are now sent to Italian specialists through a telemedicine platform. In the last 2 years hundreds of EEG recordings and more than one thousand teleconsultations requests have been sent to epileptologists in Italy from local clinicians. An increasing number of patients with epilepsy are receiving care at the DREAM epilepsy centres in the country. Personnel from healthcare centres and hospitals of the Malawi Government were part in the teaching courses.

These activities accomplish the WHO Intersectoral Global Action Plan 2022-2031 on epilepsy and the course was an unique opportunity to explain and raise awareness on the plan.

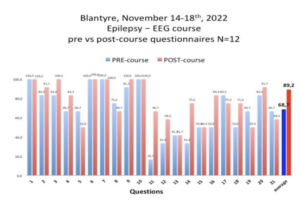

The General Director of the Kamuzu hospital, the main hospital in the capital Lilongwe, requested DREAM to further train their healthcare personnel on epilepsy to include training on EEG. The first teach and training course on epilepsy inclusive of electroencephalography for non-specialists was done at DREAM epilepsy centres in the country in Blantyre during a full week period from 14th to 18th november. Many of the participants were clinical officers, ie non physician clinicians who are responsible of treating over 90% of people with epilepsy in primary care. Their contribution to health care in hospitals is also crucial. Participants were 12 clinicians, 2 were doctors.

At the best of our knowledge this was the first epilepsy teach and training course to non physician clinicians in Malawi inclusive of electroencephalography (photos 3 and 4). Staff from other health institutions did also attend, such as Queen Elisabeth Hospital (the Blantyre University Hospital), and Saint John of God, an important health hub with several branches in the country.

The course dealed with various topics identified based on the needs of the clinicians: how our brain works, anatomy and principles of brain pathophysiology, basic mechanisms of epilepsy, motor and sensory system, weakness and numbness and their relation to epilepsy, epilepsy: epidemiology and clinical presentations, main differential diagnoses, principle of treatment: generalized and partial epilepsy. We also carried out sessions with clinical cases, some of which were selected by the participants themselves, starting from their experience in the field. Other topics of the course included: teleneurology for epilepsy, basic knowledge to understand electroencephalography, basic knowledge to interpret electroencephalography; the major epileptic syndromes in primary care such as epilepsy and fever, epilepsy without fever, epilepsy and weakness and/or numbness, epilepsy and headache, epilepsy and changes in behavior, etc. There were several practical electroencephalography sessions performed on patients.

Here are reported a few comments from the participants: “we did not expect a course like this, we had never received anything like it before“; “we understood that the electroencephalograph is not enough for a correct classification of the patient with epilepsy. We now better understand the importance of collecting history, the anamnesis“;.”we are neither neurologists nor do we have the possibility of dealing with specialists: alone we cannot go far“. The latter sentence challenges neurologists to not leave local healthcare workers alone, clues for future IGAP developments in sub-Saharan Africa.

Continuing the work in primary care: task shifting, task sharing, training on-the-job. Facing real life issues: patients stop taking antiepileptic drugs; epilepsy and pregnancy

After the course, the training activity continued on the field by sharing the work with the non physician clinicians (in Malawi they are called clinical officers) of the DREAM centers of Kapire, Namandanje and Balaka rural centers where the number of patients with epilepsy under care is growing

Jeremy (imaginary name) is a child suffering from epilepsy, I met him the first time on february 2021 at DREAM Kapire centre (https://bit.ly/EpilessiaMalawifebbr2021). Thanks to a proper diagnosis and treatment he became seizures free. In november 2022 I was in Kapire and I knew that he suspended the treatment: Jeremy’s family was convinced by local healers to suspend treatment to return to a traditional approach, rituals, and some herbs. It is not easy to change traditional, popular beliefs. He lives several hours’ walk from the DREAM center in a poor area. Such events also happen among HIV+ patients and in those cases suspending treatment is a death sentence. Retention in care is a serious issue in patients’ under treatment for chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes etc). There is a lot to work on, but the DREAM operators certainly don’t give up. In about 20 years experience with HIV/AIDS DREAM operators have obtained very good results in patients’ retention. This makes them confident to obtain similar good retention also in people living with epilepsy (PLWE).

More than half of the African population is under the age of 20, and each woman gives birth to an average of 4.4 children; throughout Africa maternity hospitals are key structures for health systems, places where women gather and receive basic health information that otherwise seldomly receive at school. The Kapire DREAM center is located near a maternity hospital. From the nearby maternity hospital, they sent us a young girl, Chicombe (imaginary name), who is just 18 years old and pregnant. At the age of 4, she had cerebral malaria. Since then, she suffers from recurring seizures. She was used to receive free medicines, phenobarbital, thanks to an NGO; but the NGO no longer operates in the region for 4 years now. For her, levetiracetam would be necessary, safer for mother and child during pregnancy, but cannot be found in the public service; and on the private market, it costs a lot: for a year of treatment, no less than €420, the equivalent of more than 6 months’ pay (the annual GDP per capita is $634.8 https://data.worldbank.org/ country/Malawi). At DREAM, Chicombe immediately starts treatment with levetiracetam. In Africa there are millions of young women with epilepsy; taking good care of mothers’ health guarantees safer pregnancies, reduced risks at delivery safe breastfeeding and healthy children eventually also contributing to reduce risk factors for epilepsy in children.

The Kapire region was not the only one left without epilepsy care. First COVID, then the war in Ukraine have much reduced aid to Africa and various NGOs are no longer able to support health care programs. Monica, 7 years old, lived in a rural region on the border with Mozambique. She had gone to the river to collect water, she had a seizure and drowned in a few centimeters of water: she had run out of antiepileptics. There is urgency to intervene.

How care for patients with epilepsy is changing

The Kamuzu Hospital (photo 10) (named after one of the country’s presidents – (https://www.kch.gov.mw) in the capital Lilongwe, has about 700 beds, 140 of which are internal medicine where patients with epilepsy are hospitalized, ≈10 per week, ≈ 500 per year (personal communication from the health professionals at the course). There are no neurologists.

Ninety % admitted patients with epilepsy is for “chronic primary epilepsy”, ie patients with very frequent daily seizures, almost always due to the interruption of treatment caused by the great difficulty in finding drugs. Stock interruption of antiepileptic drugs may occur during the year lasting several weeks/months so that the same patients need more admissions. Status epilepticus is observed. In the outpatients’ department (OPD) there is an outpatient clinic dedicated only to patients with epilepsy: this is an exception since, as it occurs in all Africa, patients suffering from epilepsy and patients suffering from psychiatric diseases are usually seen in the same place by the same health personnel (https://bit.ly/EpilessiaMozambico). In the Kamuzu Hospital OPD around 1500 patients with epilepsy are regularly followed, two thirds are under 18. Before the age of 14, they are entrusted to pediatricians.

Both Kamuzu Hospital and Saint John of God have an EEG machine, but the health personnel informed us that those machines are not in use. In the other large hospital in the country, the Queen Elisabeth in Blantyre, there is an EEG mainly used for research purposes.

Until 3-4 years ago operators of the Saint John of God hospital (https://www.sjogfoundation.ie/aboutus) (photo 11) were used to reach thousands of sick people across territory distributed in 17 vast areas of the country, predominantly patients with epilepsy thanks to a mobile clinic. Today, they can only provide care to five areas. Remaining patients are referred to government health centers which are not easy to reach. They may lack medicines, and this frustrates the patients’ expensive journeys (there is no public transport in Malawi, as in all of Africa), thus dampening their hopes. In those centers, doctors are very rare, with no specialists. The number of patients with epilepsy with poor access to care services is growing.

About 50 km from the capital Lilongwe, there is the Dzaleka refugee camp, built to house 10-12,000 people. It welcomes more than 52,000, 45% women, 48% children, with around 300 new arrivals per day.

Many come from the unstable Great Lakes region: Democratic Republic of Congo (62%), Burundi (19%), and Rwanda (7%). The number of refugees from Mozambique is also growing because of years of raids by an undefined Islamic jihad which is devastating the north of the country, an area almost the size of Italy, and which has so far resulted in 800,000 displaced individuals and 4,000 dead. Until a few years ago, the operators of the Saint John of God went regularly to the Dzaleka camp, but not anymore. There remains a twice-weekly service where they receive the sick from the camp at their city headquarters in Lilongwe.

Perspective of people living with epilepsy in Malawi and sub-Saharan Africa

In the last 20 years, sub-Saharan Africa population almost doubled, as in Malawi. A similar increase affected many diseases including epilepsy whose treatment gap (patients without access to treatment they need) exceeds75-80% of the patients leading a 3-6 times higher mortality than elsewhere. In less than 30 years, the inhabitants of those countries will double again as well as the patients with epilepsy: this urges answers

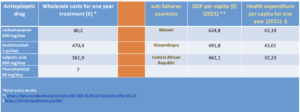

Stock interruption of antiepileptic drugs lead an increasing number of people living with epilepsy to buy the drugs by their own pocket. In the figure the prices of some antiepileptic drugs in some sub-Saharan African countries are reported along with GDPs per capita.

- Antiepileptic Drugs

Spending on antiepileptic drugs.

One year of treatment with carbamazepine (600 mg/day) costs €60.2, one year of treatment with levetiracetam (1 gram/day) costs €470.4, one year of treatment with valproic acid (600 mg/day) costs 161 ,9€.

The cheapest is phenobarbital, €7 for one year treatment at 90 mg per day. In sub-Saharan Africa the most frequent epilepsy is partial epilepsy often with secondary generalization,and phenobarbital does not seem to be the most suitable drug (it would not be so for other reasons too). A pack of acid syrup valproic – about 1 month of care for a child – costs no less than €7.7, the equivalent of 6 and a half days of an average monthly salary in the Central African Republic and Malawi, as in many other sub-Saharan countries where the average wage is similar. The number of working days needed to pay for a month of carbamazepine treatment rose to 11.8; it takes 12.9 days of work to pay for a neurological visit, 32.3 days to do an electroencephalogram, about one year of work for a year of treatment with levetiracetam.

Given the chronic shortage of antiepileptic drugs in government facilities, patients often have to buy by themselves, and retail costs are doubled (photo 14). In 2022, Malawi spent USD 42.14 on the health of each citizen, of which only USD 11.24 from the government itself, the rest was foreign aid (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/fgh/; https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.PC.CD?locations=MW), not sufficient to cover the costs of one year antiepileptic drug treatment except for those who take phenobarbital. How much should Malawi spend to treat its patients with levetiracetam? Assuming a prevalence of epilepsy at 1% (estimates are 2.4%) Malawi would have 200,000 people with epilepsy; expecting to treat them all with 1000 mg of levetiracetam per day, the cost would be 85.7 million €/year which is equivalent to 0.68% of the GDP (12.6 billion USD in 2021). The total health care spending for 200,000 Malawi inhabitants is 8.4 million euros a year, ten times less what is needed to treat 200,000 people living with epilepsy. Forecast says that in 2050 the situation will not be much different since Malawi’s per capita/yearly health expenditure are expected to rise USD 8.6 (total USD 50.72 per year): what will happen to epilepsy patients between now and 2050? Is there anything we can do?

The sale of retail antiepileptic drugs is almost half of total sales (46.1% in 2021) and it is growing globally; this is also happening in sub-Saharan Africa (Jacobs K et al. South African Family Practice 2016 DOI: 10.1080/20786190.2016 .1148337) confirming local government insufficiently provide antiepileptic drugs. Considering the mean GDP in those geographic areas the question arises: how many potentially child bearing women (but not only) in that continent will be able to afford levetiracetam to prevent risks?

The drug market

Despite millions of patients waiting for treatment, market for antiepileptic drugs is not interested in sub-Saharan Africa global market for antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) is increasing: in 2021 it was estimated at US$16.5 billion – 20.8% of the US$79.4 billion global neurological drug market – which grew to US$17.3 billion in 2022. In 2021, the global market of the first-generation AEDs (the only ones available in sub-Saharan Africa including phenobarbital, carbamazepine and valproic acid; topiramate is almost not available in sub-Saharan Africa) was 4.9% of the total AEDs market. The low economic benefit for the companies discourages companies to invest in the AEDs African market.

Things might be changing. For example less than 30 years ago, in 1995, China’s GDP was not much different compared to sub-Saharan Africa; today China GDP is 10 times bigger attracting investments much more than before. Could Africa grow in a similar way in the next future? This and the huge need should convince stake holders to invest more in the AEDs market so to improve lives’ of millions patients.

The HIV/AIDS story in sub-Saharan Africa can show a path also for epilepsy

The history of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa can teach something. In 2005 less than 4% of the about one and a half million HIV+ patients in Malawi had access to antiretroviral treatment. Later on thanks to adequate plans and investments an increasing number of HIV+ patients could access the treatment so that today over 90% of them receive the drugs. A change is possible.

- If the problem is circular

Drug shortage limits adequate training

The poor availability of antiepileptic drugs in sub-Saharan Africa has several consequences. It leaves patients untreated and at the same time does not allow healthcare personnel to become familiar with the management of the disease. It also reduces the impact of both teaching courses and the invested resources as well. Well-treated seizure-free patients bring the potential to witness the non-magic nature of the disease and at the same time show that epilepsy can be won. A poor availability of antiepileptic drugs is a bottle neck leaving the disease as it is socially seen now.Also an appropriate access to treatment helps awareness campaigns to fight the plague of social stigma.

Mental illness and epilepsy

In many African regions, epilepsy is still regarded as a mental disorder, often a curse, even contagious: it’s scary, and the sick are isolated, mistreated, stigmatized. Until recently patients suffering from epilepsy and patients suffering from psychiatric diseases were treated in the same place by the same health personnel. In the long run this have had draw backs. These centers are lacking in personnel, education and training, drugs, equipment, so that the stigma did not improve. This approach (to manage both the conditions in the same place with the same personnel) was mainly justified due to the lack of resources, sustainability and cost-effectiveness became the leading idea so that stake holders did pay insufficient attention to the dignity of the patient. It is worthy saying that not everything that currently saves money turns out to be a good investment.

If awareness goes with care

How would an information-awareness campaign be perceived in communities with poor access to treatment?

We have seen this with HIV: if awareness is not followed by improving access to treatment trusting in the institutions suffers. Conversely, available medicines offered by trained and motivated personnel can turn the tide and change the lives of patients.

Guaranteeing continuous supplies of antiepileptic drugs generates trust and hope among patients and the population in general.